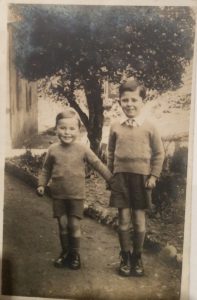

My late father Kingsley Squire and his elder brother Geoff, who still lives in Devon, were fortunate enough to grow up in Branscombe, a quintessential English village by the sea. Living in the schoolhouse, where their father Stanley, was headmaster, they were given freedoms today’s generations will never know… Here are two extracts from his series of memoirs Branscombe Voices from the 1940s, Geoff takes us back to those halcyon days…

By Geoff Squire

The Natural World

I was fortunate to grow up in the schoolhouse Branscombe where the wildwood, with its great springtime

dawn chorus of birdsong, began about twenty yards from our back door. In the 1940s our parents were happy to let my brother Kingsley and me roam freely, provided we didn’t get our feet wet too often. It’s not surprising that we spent hours and hours exploring this little wood and rambling around in the patch of countryside that lay beyond it – we called it ‘going up over’- an ideal life for two small boys.

Our patch was the area around the schoolhouse the hill behind it and the valley stretching away to the north. A network of paths and lanes led us to more extensive woodland, small green fields with vigorous hedgerows, bramble patches, little pools and swamps down by the stream, disused quarries and bracken

covered hillsides on the higher ground. There were tall trees for climbing, smaller trees and bushes for tree houses, a sandpit, hiding places, dens and lookouts in our favourite spots……all this was our playground!

Moving around our patch we knew where to find frogs and frogspawn, tadpoles and newts, butterflies, moths and dragonflies, rabbits, slow worms, adders and rats. Moles also interested us when they came into the garden – they really annoyed my father when they damaged the lawn. Mucking about by the stream we came across all sorts of beetles and bugs and sometimes there was something to eat – hazelnuts, clean watercress, field mushrooms, blackberries, elderberries, wild strawberries, wild crab apples and even eating apples. I’m sure that crab apples must taste better when they are made into jelly.

Out and about throughout the year we noticed seasonal changes in the appearance of our patch – we knew about the autumn leaf fall and that some trees keep their leaves in winter. Shiny conkers were collected at Barnells in the autumn as were fallen leaves for garden compost. In winter the old family pram was useful for bringing home firewood from Hole Copse. Wild daffodils and primroses coloured each spring and every year many house martins and a pair of swifts arrived to nest under our eaves, so our 1940s summers were filled with the sounds of screaming swifts as they raced across the sky chasing insects and the twitterings of numerous house martins whirling around the house and school – fantastic.

An early edition of the Observer’s Book of British Birds, which I still possess, helped us to recognise migrants and residents in our patch, their calls and nesting places – chiffchaffs, willow warblers, whitethroats, blackcaps, yellowhammers, treecreepers, green woodpeckers, buzzards, jays……. In the 1940s cuckoos were often heard and sometimes seen in Branscombe and one afternoon an exhausted cuckoo landed on our shed roof near the back door, perhaps it had just flown in from Africa – the poor bird was flat out and it took some time to recover. These days Devon cuckoos are mainly confined to Dartmoor.

When we were old enough to ride our bikes around the village the boundary of our known world expanded to include Street in one direction and the Square in the other, two new ‘districts’ for us, but we began to spend more of our time around Mill Farm, a working farm just down the hill from the schoolhouse. Now called Manor Mill, in the 1940s it was the home of David Dowell and with David we explored the cogs and workings of the old corn mill, the waterwheel and millstream, the fields and woods above Mill Farm and the old rookery on the hill down towards Branscombe Mouth. At that time this rookery was full of activity but I believe the rooks moved to a new rookery further up the valley a few years later. There were dippers bobbing about by the millstream, darting to and from their nest behind the waterwheel, colourful grey wagtails, chaffinches in the orchard and swallows swooping in and out of the barn where they nested year after year. One snowy winter we had an exciting time sledging on one of the steep fields above the mill.

So with increased mobility, our known world was gradually expanding. Even so, large areas of the parish remained remote and largely unknown – well beyond the edge of our orbit and only glimpsed from time to time through the window of the Southern National bus on the rare occasions we travelled from the bus stop at the Post Office to Seaton or Sidmouth. On these journeys I wanted to know just where Branscombe began and ended. After travelling in the bus for some time I would ask about this,“Mum, are we still in Branscombe?” “I think so”, was her usual reply as the bus trundled on through the countryside.

As far as I remember, I’ve never set foot in Watercombe, Young Coombe (known as Yuncum) or Great Knowle and I still have little first – hand knowledge of the high ground surrounding the Branscombe valleys. Along the southern edge of the village the beach at Branscombe Mouth was inaccessible because it was mined and sealed off due to the threat of invasion. In the interest of safety we were forbidden to go near the cliffs – a rule we didn’t always observe, but we knew about the dangers.

However, one day it became clear to us that something new was in store. For some reason my father had decided that he wanted to try his hand at prawning and the best place for that would be the rock pools at Branscombe Ebb. Lying half a mile or so west of Branscombe Mouth, Ebb rocks had a reputation as a good prawning ground, but we needed to choose a day when the weather and tides were right for us. At last that time arrived and on a sunny summer morning, accompanied by Grandma age 70+, we all set off for Ebb rock pools, the first of many visits. Loaded up with our prawning nets, buckets, packed lunches and thermoses full of tea we made for the footpath up through Church Copse and out towards the sea.

Suddenly we were there – a small family group on the edge of an enormous cliff over 300 feet above the sea, admiring the splendid panorama before us – the great sunlit sweep of Lyme Bay, sparkling from the far south of Devon on our right all the way around to the Dorset coast and distant Portland Bill on our left.

Then, another surprise – a glistening pod of leaping dolphins came into view cutting through the water at terrific speed, heading up-Channel not far offshore …. a breathtaking sight on such a beautiful morning. After a pause came the questions. Is a dolphin a fish? Can we name places and landmarks around the bay? Why are the cliffs so red? – a cue for another favourite book – ‘Britain’s Structure and Scenery’ by Dudley Stamp, first published in 1946. How far is it to Portland over there? to France across there? and what about Torquay, Dartmoor, America in the other direction…..? So much to take in – a whole new geography!

But we couldn’t stay up there for long – we were working to a timetable, one based on the tides – you can’t find prawns when the rock pools are covered, you need to go at low tide when they are exposed. We knew about this timing for the day of our visit from my father’s enquiries in the village. I suppose that today he would just look up tide tables online.

With seagulls wheeling overhead we slowly wound our way down the narrow cliff path passing some cliff gardens (further questions) on the way. We reached the rock pools as they were opening up on the falling tide. Our timing was good and having ‘caught the tide’ we quickly set about the task of catching prawns. This was not easy because prawns are very crafty – they are smart movers, especially when they suddenly jump backwards or sideways. Sensing the slightest disturbance in their pool they can rapidly conceal themselves in crevices and your net comes out of the water full of seaweed and small stones – you certainly need patience! Getting a good catch is quite an art and it took some time to work out just where to go on the rocks and how to use a net to get the better of these elusive creatures.

There were more questions – the mystery of the tides, the marine creatures and seaweeds in the rock pools, the odd behaviour of hermit crabs and….how did those limpets attach themselves so firmly to their rocks? As always, my father was a reliable source of information and he turned out to be pretty good at prawning – wading around in the rock pools, prawning net in hand and trousers rolled up to his knees.

After a few hours of this the tide turned and gradually the rock pools began to disappear, a clear signal that it was time for us to go home. So we packed up and keeping a watchful eye on Grandma, trudged up the steep cliff path. At the top, a pause for breath and a last look back over Lyme Bay – still sunlit and gleaming….. Then, on our way down past some huge beech trees at the top of the Church Copse footpath my father said “Look down there, you see that nothing much grows under beeches”. This is something I’ve noticed about other beech hangers over the years, but the carpets of bluebells under beeches in the Chiltern Hills year after year in early May were a delight. Arriving back at the schoolhouse we reflected on an exciting but tiring day which had shown us new aspects of Branscombe, an attractive extension of our known world and much speculation about what lay over the horizon.

Looking back on these early memories I can see that over time my mental map, my personal geography of Branscombe, emerged and gradually enlarged. Attachment to our patch around the schoolhouse in the early 1940s gave us a feeling of security when we knew that a terrible war was raging in the wider world. As for the longer term, I am aware that the experiences I’ve described have helped to shape some lifelong interests, the course of my education, working life and identity.

Now, after seventy – five summers, are house martins and swifts still nesting under the eaves? Are there dippers down by the waterwheel? What has happened to the Devon cuckoos and the dolphins? Do people still go prawning at Branscombe Ebb? Do Branscombe children still ramble around their patches discovering the natural world?

Charlie Taylor (1869-1958) Cobbler

During the war-ravaged ‘Make Do and Mend’ years of the early 1940s we depended on Mr Taylor, Branscombe’s village cobbler to keep our footwear in good order. So my destination, boots over the handlebars of my bike, was his workplace in the front room of his small stone – built cottage up the road at Street near the Fountain Head pub. My instructions: ‘Boots to be soled and heeled, with Blakeys please Mr. Taylor’. My father favoured Blakeys because they prolonged the life of our boots. My brother and I liked them because of the noise and sparks they made.

Once again Mr Taylor was at home, working away at his tall last, making the most of the daylight coming in through his tiny front window – just where I had left him at the end of my last visit a few months ago. As usual, his room was filled with the distinctive smell of rubber, leather, glue and fumes from the heated black wax he used for waterproofing. On hand were his cutting, shaping and finishing tools and on the floor a jumble of rubber and leather offcuts, partly completed jobs, cans of various substances and other oddments.

Away from the window the recesses of the room were always pretty dark but I was aware of a few pieces of furniture. On the wall were several large framed pictures suspended on long strings from hooks on a high picture rail – panoramas of famous 19th century naval battles and other maritime scenes which looked like dusty reminders of Trafalgar days…. Had Mr Taylor served in the navy – another life in distant parts of the world?……..

I watched Mr Taylor as he cobbled away on his tall stool, finishing off a repair with the black wax he carefully brushed around the edge of the sole and heel – an elderly, grey man still taking a pride in his work. From previous visits I had the feeling that he did not welcome interruptions when he was completing a job, but after a time he stopped working. Taciturn but not unfriendly, he picked up my boots, looked them over, thought for a moment and then in his rather gruff Branscombe voice said ‘Come back in a week and they’ll be done’. With that he turned back to his tall last by the window and carried on cobbling. Mr Taylor needed this tall last because he was a very tall man. I said goodbye to him, closed the door, got on my bike and set off for home – all down hill from Street, except for the last bit up School Lane.

For many years Charlie Taylor provided an essential footwear repair service for the people of Branscombe and as far as I knew in the early 1940s that was his entire world. I was wrong – because 75 years later, I know that he was a Methodist Lay Minister. I was also surprised to learn that he was the postman for the western section of the parish, an extensive area of scattered farms and houses set in hilly terrain and connected by a network of long meandering footpaths and straggling lanes.

Comments by people who knew him well mention his legendary reputation for collecting and delivering the mail on time and the quiet dedication he needed to complete his rounds in all winds and weathers. It appears that in order to cope with the terribly muddy conditions of winter he wore old-fashioned wooden ‘ pattens ‘- wooden platforms attached to his boots enabling him to wade through thick mud.

Like many Branscombe people at that time Mr Taylor needed more than one job in order to get by.

There is more about this and other aspects of village life before 1960 in the excellent

Branscombe Project 2000 publication ‘Branscombe Shops, Trades and Getting By’ Edited by

Barbara Farquharson and Joan Doern.